In The Scout Mindset, Julia Galef argues against having a soldier mindset — Galef’s term for motivated reasoning. Instead, she argues we should aim to have accurate beliefs, which Galef calls this the scout mindset. I enjoyed the book, but I think Galef's characterization of the soldier mindset conflates two distinct properties: motivated reasoning and what I'm going to call combative reasoning. I think motivated reasoning is generally bad, but combative reasoning has its virtues.

What is motivated reasoning?

Evidence, testimony, and good arguments give us epistemic reasons to believe things because they make our beliefs more likely to be true. The prospect of satisfying our personal desires and the prospect of doing good give us non-epistemic reasons to do things because they make our actions more likely to achieve good outcomes.

We engage in motivated reasoning when our beliefs are directly influenced by our non-epistemic reasons. If you want your local school to get more funding and this causes you to uncritically believe every study that finds a link between school funding and performance, you are engaging in motivated reasoning. Since non-epistemic reasons don’t generally make our beliefs more accurate or more likely to be true, most people think motivated reasoning is irrational.1

Combative reasoning

Although Galef equates the soldier mindset with motivated reasoning in the opening chapter of the book, I think many of the descriptions of the soldier mindset don’t involve motivated reasoning in the sense I’ve described above. Consider the properties of a soldier mindset listed in the table below:

I’m going to focus on the first, third, and fourth of these properties. In other words, people for whom the following are true:

Reasoning is like defensive combat

Finding out you’re wrong means suffering a defeat

Seek out evidence to fortify and defend your beliefs

Assume for now that if you have each of these properties, you’re engaging in what I’ll call combative reasoning. Here are two initial cases to illustrate why I think combative reasoning isn’t the same as motivated reasoning:

Alan’s astrological beliefs (non-combative ⇏ non-motivated)

Alan believes in astrology because he gets comfort from the belief. When pressed on whether he thinks it actually works, he just says “well, we all have our opinions”. He doesn’t feel the need or desire to defend the belief, seek out further evidence for it, or avoid evidence against it.Emma’s economics beliefs (combative ⇏ motivated)

There’s heated back-and-forth in an economics journal in which Emma, an economics professor, argues that the minimum wage should be increased against others who believe that it should remain the same. Emma doesn’t have much practically at stake in how this question turns out, but she wants to win the argument about the minimum wage. She seeks out and presents evidence that supports her claims, counters the points made by her opponents, and would feel shame if she were shown to be wrong in any of her key points.

Alan is clearly engaging in motivated reasoning, but he doesn’t seem to be engaging in combative reasoning—he isn’t doing any of the three things mentioned above. Emma is clearly engaging in combative reasoning—she is doing all three of the things mentioned above—but she isn’t obviously engaged in motivated reasoning. She is at least not engaged in the same kind of motivated reasoning as the person who uncritically believes all the studies linking school funding and performance.

What motivates combative reasoning?

I’m suggesting that combative reasoning isn’t necessarily the same as motivated reasoning. But someone reading this claim might ask why Emma would be so defensive of her beliefs unless she has personal reasons for wanting her particular beliefs to turn out to be true, rather than just wanting to have true beliefs in general.

Even if she doesn’t have much at stake in the object-level question, Emma probably has many personal reasons to be defensive of her beliefs. She may want other experts to think her views on the minimum wage are correct, she may want journal readers to think she is clever and not liable to make shoddy arguments, and so on. So perhaps her combativeness is the result of motivated reasoning after all.

Reply 1: Motivated reasoning is only as bad as your motives

The difference between Emma’s case and a “typical” case of motivated reasoning is that, in a typical case, the personal benefit someone gets from belief or disbelief is mostly uncorrelated with how accurate or inaccurate their beliefs are. Alan believes what is comforting, but beliefs can be comforting without being accurate.

But the desires attributed to Emma above are closely connected with having accurate beliefs. If you want other experts to believe you’ve adopted a correct position, it’s a good idea to try to have accurate beliefs. If you want people to think you’re clever and not liable to make shoddy arguments, it helps to have accurate beliefs. In other words, Emma has accuracy-promoting desires while Alan does not.

Consider an analogous case in the moral domain. Suppose Jane is only motivated by a desire to do good, while Tim is partly motivated by a desire to do good and partly by personal desires that are closely connected with doing good. He wants to be remembered as a good person, to have others think of him as a good person, and so on.

How should we “grade” these two motivational profiles, morally speaking? I think it mostly depends on how much good each person does. This in turn depends on how strongly each person is motivated by their desires, how connected their desires are with the thing we care about, and how robust that connection is. If Jane's only desire is to do morally good things but she isn't particularly motivated by this desire, Tim might end up doing more good despite having less “pure” motives.

Similarly, if Emma is more motivated to improve the accuracy of her beliefs because her reputation is at stake, she might acquire more accurate beliefs across a wider set of domains than if she were to adopt a scout mindset and be motivated by accuracy alone, since this would mean she was less motivated overall. Of those who have made important scientific discoveries, I’m sure many have been at least partly motivated by recognition. Of those who have highly accurate beliefs, I’m sure many have been at least partly motivated by a personal dislike of being shown to be wrong.

Perhaps in an ideal world we would all only be motivated by epistemic accuracy and moral virtue, and we would be more motivated by this than by any kind of self-interest. But in the real world I think we should judge motives by what they produce. If a desire look impressive or appear right causes people to have more accurate beliefs or produce more scientific discoveries, I won’t argue people out of those desires.

Reply 2: People can be combative for non-selfish reasons

The reply above assumes the objection is correct, and that Emma is motivated by self-interested reasons that are connected with accuracy but not identical with it. But we don’t need to grant this. It’s possible that Emma truly values accurate beliefs above all else, but thinks that engaging in combative reasoning is a good strategy for her to acquire accurate beliefs on a wide range of questions.

The idea that combative reasoning could promote accurate beliefs seems pretty defensible. If we feel compelled to engage in epistemic combat and we feel shame when we lose, we’re likely to spend time seeking out new strategies for succeeding, to try to find holes in other people’s strategies, to acquire more resources like evidence in our arsenal, and so on. Treating epistemics as an adversarial game creates competitive pressure for us to explore and to improve our beliefs and our strategies.

This isn’t to say that it’s always better to reason combatively. There are many contexts in which combative reasoning is stifling or actively harmful, and where collaborative reasoning is much more fruitful. But I also don’t think someone solely driven by having accurate beliefs will necessarily reject combative reasoning.

The conditions for good epistemic combat

People might argue that we tend to polarize: to divide into groups and to simply cheer on whoever defends the views we like. So reasoners like Emma who want to impress others will start to defend views of one particular group, rather than what is true.

I think this is a fair concern. But if observers are even mildly attuned to the truth then having correct views in a debate is a bit like having strong calf muscles in a gymnastics competition: these alone won’t win you the competition—someone with weaker calf muscles and better cardio health could easily beat you—but they’re still an advantage. Impressive orators who tell people what they want to hear will hopefully lose in the long-run to those who are both impressive orators and also correct. (Or as Schopenhauer put it, winning a debate is all the easier if we are actually in the right.)

Of course, this assumes that when people polarize, they don’t stop caring about truth entirely. What if people’s beliefs are driven almost entirely by non-epistemic reasons that have little or no connection to the truth? In this situation, having truth or convincing arguments on your side might be of no advantage to you. I agree that combative reasoning stops leading to accurate beliefs if people’s judgments of success become sufficiently detached from the truth in this way.

This places a constraint on when combative reasoning leads to more accurate beliefs. But I’m tentatively optimistic that people are subject to the first kind of polarization more than the second. Those on different sides of an issue are often reasonable when they’re engaged reasonably. And having true beliefs creates practical advantages that it’s not in our self-interest to ignore forever—e.g. an ability to successfully create new technologies or develop scientific breakthroughs. Finally, the truth often makes itself known to us in ways that are hard to keep denying, whether through successful predictions or simply by sitting right in front of us.

Paladins and pacifists

I’ve argued that combative reasoning can lead people to develop more accurate beliefs. I’ve also argued that people can engage in motivated reasoning without being particularly combative.

I’m going to use two terms for each of these roles. Pacifists are people like Alan who engage in motivated reasoning but are not combative reasoning. Paladins are people like Emma who engage in combative reasoning but are motivated by accuracy or by things closely connected with accuracy. Soldiers may fight for whatever battalion they find themselves in but—as any D&D player knows—paladins fight only on the side of justice and the light. (And I suspect that epistemic paladins, like D&D paladins, can also be kind of annoying to interact with.)

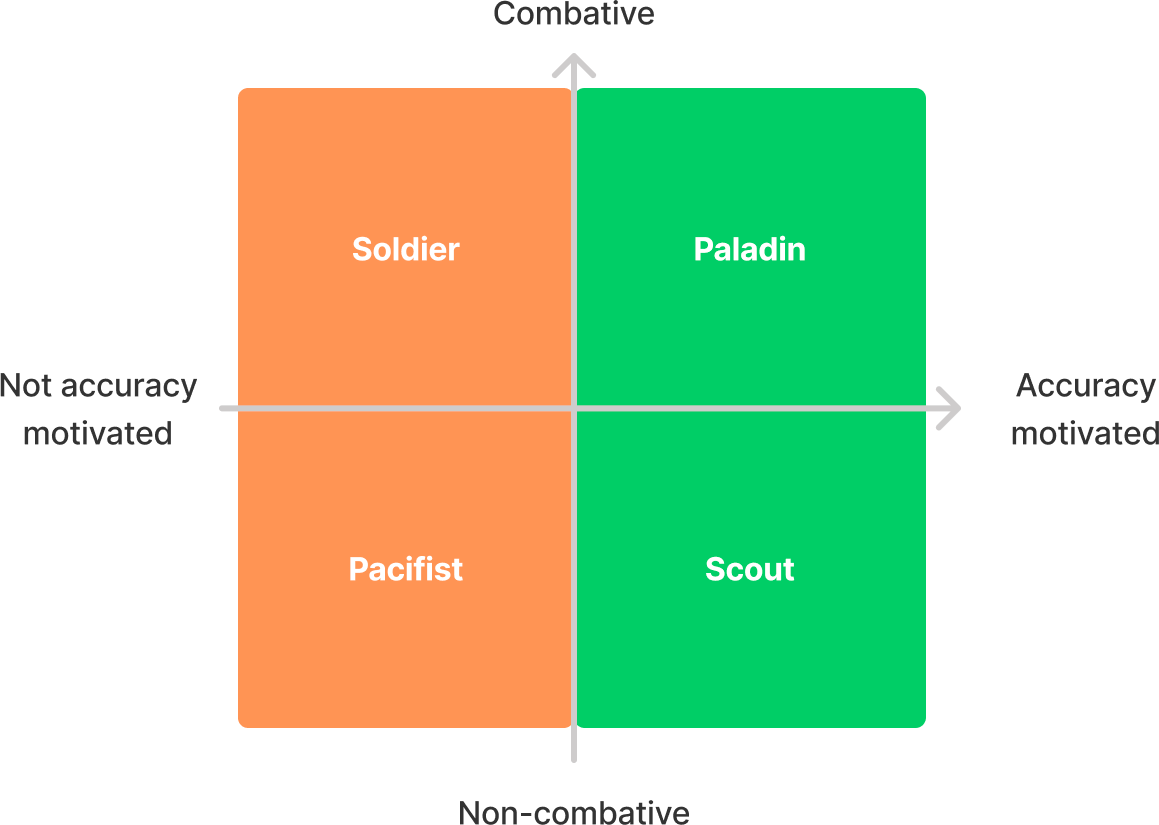

So here’s how we might expand the solder/scout framework if we distinguish being combative from being accuracy motivated:

I think the soldier/scout framework can cause us to overlook the virtues of being a paladin. But it also overlooks the badness of being a pacifist. The soldier at least feels the need to defend their beliefs. This means we can engage with them and perhaps even change their minds or the minds of those observing our debate. They are at least playing the game, even if they’re not doing so in good faith.

But the pacifist doesn’t feel the need to engage at all. They can happily sit on an island of inaccurate beliefs, unswayed by any scout or paladin or soldier that passes by. If the truth offers any advantage in arguments, it may be preferable to live in a world full of soldiers than in a world full of pacifists.

Group rationality and individual sacrifice

The kinds of preferences that the paladin typically has—to appear impressive and correct—don’t just incentivize believing whatever is true. They incentivize trying to discover and defend truths that others haven’t yet discovered or defended.

In philosophy, there’s a tendency to defend views that can seem wildly implausible. I think this is partly because it’s much more impressive to successfully defend an implausible claim than a plausible one. It’s also more impressive to make a novel empirical discovery than to find additional evidence for a previous one.

For this reason, people motivated by appearing impressive or far-seeing can be motivated to explore new areas even to the point of individual irrationality. They can end up defending contrarian views that are very likely to be false, or trying to find evidence for very implausible empirical claims. Taking on this kind of risk may be worth it, since they’ll get a big payout if they’re correct.

I think this kind of exploration is often good for the epistemic health of a group, even if it’s irrational on the part of individuals.2 And group rationality is often sadly neglected in favor of individual rationality. In groups, people play a variety of different epistemic roles: some explore new territory, some dive deeper into already-explored territory, some attempt to defend new territory, some keep everyone sharp by fighting them, and others seem to be slacking off or actively burning things for no reason.

The rationality of groups may turn out to be more important than the rationality of individuals, for roughly the same reasons that the efficiency of large firms may be more important than the efficiency of the individuals within them — the actions of collectives can be more consequential than those of individual actors.

I wouldn’t be surprised if a community made up of purely rational and accuracy-driven individuals were to turn out to be irrational at the group level, in practice if not in theory. In theory, purely rational individuals could recognize that their individual rationality was bad for the group and adjust their behavior. In practice, this requires a lot more reasoning steps than “I want to win a Nobel Prize”.

Note that we aren’t necessarily engaging in motivated reasoning if our beliefs are indirectly influenced by our non-epistemic reasons. Suppose you want your local school to do well, so you look up all the studies you can find on how much school funding improves performance. Your beliefs about school funding will be affected by these studies, and will be different from the beliefs you would have had if it weren’t for your preferences. But if you rationally respond to the studies about school funding—if your beliefs are directly influenced by your epistemic reasons in the right sort of way—we generally think they can still be rational. See Vavova, 2016 for a more extensive discussion of these issues.

See Kopec 2019-2020 for an example of work on what constitutes group rationality.

The social value of combative reasoning depends entirely on whether it is situated within a larger system of sensemaking. The private value of high-integrity combative reasoning (vs specious arguments and bad-faith rhetorical appeals) depends on the integrity of that sensemaking.

Adversarial legal systems don't leave it up to the lawyers for the two sides to decide what's true. Judges to adjudicate procedure and decide on points of law, and sometimes separately juries decide on points of fact. By contrast, televised political debates, at least in the US, seem to have long since become an unintelligible posturing contest, such that when available it's easier to understand what's going on by watching the Bad Lip Reading versions of Presidential debates than the ones with real audio.

Noncombative reasoning motivated by selfishly wanting to understand one's own situation in order to make better decisions seems relatively though not perfectly robust to bad social norms, since the perceived benefit of accuracy doesn't depend on others' propensity to reward it.